One of the drawbacks I’ve found when dealing with Common Lisp is the lack of documentation available. Too often, I find published libraries without an explanation of how they are meant to be used or only partially documented, and I need to dig into the source code to understand what they do and to see all the functions available. Even though reading source code is a proven technique to improve one’s grasp of a programming language, most other systems come with extensively documented libraries, something appreciated by beginners and a factor that often contributes to a language’s popularity.

In my opinion, this lack of good documentation is one of the reasons Common Lisp is often seen as challenging for beginners, which makes it harder for the language to become popular.

Some time ago, when I looked for guidance on writing a generic web app, I was surprised by the absence of a quickstart page to help me set up a simple server—something the Python community has provided for Flask for many years.

“The most underrated skill to learn as an engineer is how to document. Fuck, someone please teach me how to write good documentation. Seriously, if there’s any recommendations, I’d seriously pay for a course (like probably a lot of money, maybe 1k for a course if it guaranteed that I could write good docs.)” A drunk dev on reddit

So I put together a short tutorial on how to build a simple web app in Common Lisp, inspired by the Clojure tutorial written for Luminus. The goal is to write a guestbook demo, involving template rendering, connecting to a database to run queries, and exposing routes to the webpage.

To follow the tutorial, you need a Common Lisp implementation, like SBCL, with Quicklisp, the dependency manager. I also recommend having a REPL integrated with your IDE, like SLY for Emacs or Alive for VSCode.

I’ll use more modern CL libraries that have an interface similar to other languages, so it might be a bit easier to follow along.

The server

First things first, I created a new Common Lisp project. To do that with a simple boilerplate, I loaded cl-project in the environment and called the function make-project with a path and a name for the project.

> (ql:quickload :cl-project)To load "cl-project": Load 1 ASDF system: cl-project; Loading "cl-project"..(:CL-PROJECT)

> (cl-project:make-project #P"~/guestbook/" :name "guestbook")writing ~/guestbook/guestbook.asdwriting ~/guestbook/README.orgwriting ~/guestbook/README.markdownwriting ~/guestbook/.gitignorewriting ~/guestbook/src/main.lispwriting ~/guestbook/tests/main.lispTThen I ran this command to let Quicklisp know where my new project is located.

> (pushnew #P"~/guestbook/" asdf:*central-registry* :test #'equal)I declared the required libraries in the :depends-on property so that Quicklisp would download them from the repo and load them into the environment.

(defsystem "guestbook" :version "0.0.1" :license "MIT" :depends-on (:alexandria ;; utils :uiop :cl-ppcre ;; regex library :cl-syntax-annot ;; for @export annotation :clack ;; Web libraries :lack :caveman2 ;; Web framework :djula ;; Template engine :cl-dbi) ;; Database :components ((:module "src" :components ((:file "config") ;; files into src/ (:file "db") (:file "web") (:file "core"))))Now, inside src/core.lisp (I renamed the file from main to core) I added two new functions, to start and stop the server, which will be helpful to use from the REPL.

(defvar *server* nil)

(defparameter *app* (lack:builder (:static :path (lambda (path) (if (ppcre:scan "^(?:/images/|/css/|/js/|/robot\\.txt$|/favicon\\.ico$)" path) path nil)) :root *static-directory*) ;; Additional middlewares guestbook.web:*web*))

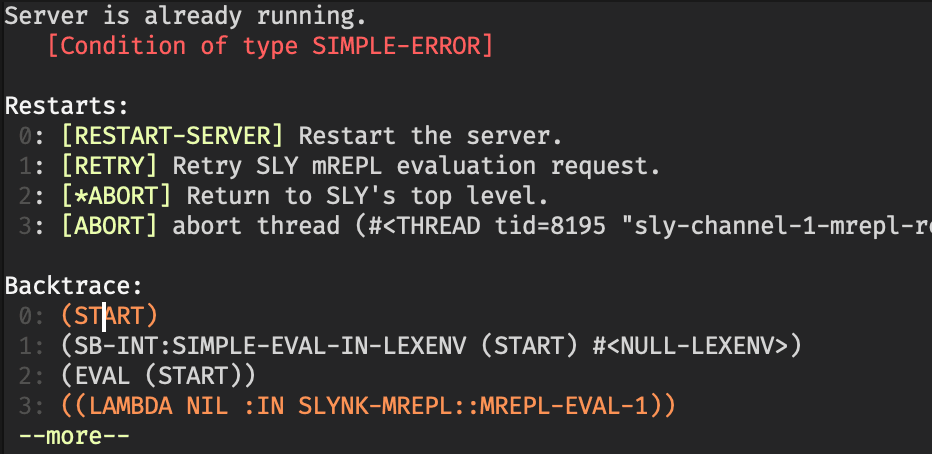

@export(defun start (&rest args &key (server :hunchentoot) (port 3210) (debug nil) &allow-other-keys) "Starts the server." (when *server* (restart-case (error "Server is already running.") (restart-server () :report "Restart the server." (stop))))

(setf *server* (apply #'clack:clackup *app* :server server :port port :debug debug args)) (format t "Server started"))

@export(defun stop () "Stops the server." (when *server* (clack:stop *server*) (format t "Server stopped") (setf *server* nil)))*server* contains the server instance and is defined as a variable since we will need to redefine it. *app* is the web application wrapped with a layer by Lack. start and stop instantiate the server with some logging, or raise errors if the action is not successful.

Lack and Clack are the two libraries I used to wrap the web application. The first one allows to define a series of middlewares in the server; for example, I used :static to tell the server where to find all the static assets in the project, inside the directory pointed to by *static-directory*. Other middlewares are available, like logging, managing sessions or providing authentication features. Clack instead is an abstraction layer for the server that provides some parameters to customise it, for example, to quickly swap which server to use between development mode (hunchentoot) and production (woo).

(unless (null *server*) (restart-case (error "Server is already running.") (restart-server () :report "Restart the server." (stop))))In this portion of the code, I defined a restart action for the debugger. The Common Lisp debugger always has RETRY and ABORT actions for every exception raised. By declaring a restart-case, we are signalling an error and adding custom choices to the ones offered by default by the debugger. The new option I added is called restart-server and, if selected, it first (stop)s the server and then restarts the operation, so the function runs again without raising an error. It’s a smart way to interact with the REPL and improve the developer experience using the language directly.

More on conditions and restart here and here.

At the top of src/core.lisp I set the package definition and some initialisation function calls.

(in-package :cl-user)(defpackage guestbook.core (:use :cl) (:import-from :guestbook.config :*static-directory*))(in-package :guestbook.core)

(syntax:use-syntax :annot)(syntax:use-syntax :annot), from the package cl-syntax-annot, allows us to use some special decoration notation at the top of the function. At the top of start and stop I added an @export tag, which tells the compiler that a function is exported by the package.

Configuration

I put the configuration parameters for the app into a config file; there are better ways, but they’re not necessary for a project this simple.

@export(defparameter *application-root* (asdf:system-source-directory :guestbook))@export(defparameter *static-directory* (merge-pathnames #P"static/" *application-root*))@export(defparameter *template-directory* (merge-pathnames #P"templates/" *application-root*))

@export(defvar *config* `(:databases ((:maindb :sqlite3 :database-name ,(namestring (merge-pathnames "guestbook.sqlite" *application-root*)))) :schema-file "db/schema.sql"))The variable *config* needs a specific format to be used with cl-dbi, which is the library that I used to interface with the database. In a real application, it would be good to differentiate between dev and prod mode with different configurations used, for example to point to different databases or to use a different server with Clack.

Database

I created a new file in db/schema.sql and put the SQL code to create a message table.

CREATE TABLE message ( id INTEGER PRIMARY KEY AUTOINCREMENT, username VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL, ts DATETIME NOT NULL, content TEXT NOT NULL);Then I ran sqlite3 guestbook.sqlite --init db/schema.sql from the terminal to create and initialise a new database in the project root.

(in-package :cl-user)(defpackage guestbook.db (:use :cl) (:import-from :guestbook.config :*config* :*application-root*))(in-package :guestbook.db)

(syntax:use-syntax :annot)

(defun connection-settings (&optional (db :maindb)) (cdr (assoc db (getf *config* :databases))))

@export(defun db (&optional (db :maindb)) "Returns a cached database connection for DB (defaults to :maindb). Uses `connection-settings` and `dbi:connect-cached`.

Usage: (db) or (db :testdb)" (apply #'dbi:connect-cached (connection-settings db)))

@export(defvar *connection* nil)

@export(defmacro with-connection (conn &body body) "Executes BODY with *CONNECTION* dynamically bound to CONN.CONN should be a database connection object, typically from `db`.

Usage: (with-connection (db :maindb) (dbi:do-sql *connection* \"SELECT * FROM users\"))" `(let ((*connection* ,conn)) (unless *connection* (error "Database connection cannot be NIL")) ,@body))This is the first macro of the project. It’s a simple wrapper that provides a new variable *connection* to use inside the body. It raises an error if the conn value that we passed is not initialised. The function db instead returns a valid connection, cached automatically by the library.

Then I defined some functions to perform CRUD operations on the database. format-timestamp converts a universal timestamp value into a readable date-time string.

(defun format-timestamp (universal-time) "Converts a universal time value into a human-readable timestamp string,formatted as 'YYYY-MM-DD HH:MM:SS'." (multiple-value-bind (sec min hour day month year) (decode-universal-time universal-time) (format nil "~4,'0D-~2,'0D-~2,'0D ~2,'0D:~2,'0D:~2,'0D" year month day hour min sec)))

(defun add-message (name message) "Inserts a new message into the database with the given NAME and MESSAGE content." (with-connection (db) (let ((sql "INSERT INTO message (username, ts, content) VALUES (?, ?, ?)") (ts (get-universal-time))) (dbi:do-sql *connection* sql (list name ts message)))))

(defun delete-message (id) "Deletes the message with the given ID from the database." (with-connection (db) (let ((sql "DELETE FROM message WHERE id = ?")) (dbi:do-sql *connection* sql (list id)))))

(defun get-all-messages () "Retrieves all messages from the database, ordered by timestamp descending.Timestamps are formatted as human-readable strings." (with-connection (db) (let* ((sql "SELECT * FROM message ORDER BY ts DESC") (messages (dbi:fetch-all (dbi:execute (dbi:prepare *connection* sql))))) (mapcar (lambda (row) (setf (getf row :|ts|) (format-timestamp (getf row :|ts|))) row) messages))))The Web App

Finally we can create the web application which I put inside src/web.lisp. It’s a bit longer then the other files so I will break it into chunks.

(in-package :cl-user)(defpackage guestbook.web (:use :cl :caveman2) (:import-from :guestbook.config :*template-directory*) (:import-from :guestbook.db :add-message :delete-message :get-all-messages) (:export :*web*))(in-package :guestbook.web)

(defclass <web> (<app>) ())(defvar *web* (make-instance '<web>))(clear-routing-rules *web*)The web framework I am using is called Caveman, developed by Eitaro Fukamachi, who is a very prolific lisper and the author of multiple libraries that I am using, including Lack, Clack, and cl-dbi, all having great integration with each other. <app> is a class defined by the web framework, and I am extending it and instantiating it in *web*. clear-routing-rules is a function inherited from Ningle, another web framework, which clears the route associations inside the web app instance.

Templates

Our web app needs to render some static templates with data, and to do that there’s a great library called djula, which allows us to use most of the same tags and filters that Django exposes in its template engine.

I’m not going to include the templates source here for space reasons, in the repository they’re in the templates/ folder.

(djula:add-template-directory *template-directory*)

(defun render (template-path &optional env) "Renders a Djula template from TEMPLATE-PATH.ENV is an optional plist of variables passed to the template." (apply #'djula:render-template* (djula:compile-template* (princ-to-string template-path)) nil env))The first function call tells djula where to find the templates in the project. render is a function that receives a template path as a parameter and compiles the template for better performance.

Routes

To allow users to perform CRUD operations, we need to expose a few routes to be called by the web frontend. There are two ways to define routes in Caveman, but this one seems a bit clearer to me than using annotations. defroute is a macro that receives the route path, some parameters like :method and eventually some arguments, and then defines the body to handle the request. Inside the body, we can access the request object via *request* and extract data from it using, for example, the function request-body-parameters.

The routes are self-descriptive. / renders index.html, passing all the messages from the db; /message handles POST requests and inserts the message in the database if the parameters conform; and /message/delete deletes a message.

(defroute "/" () (render #P"index.html" (list :messages (get-all-messages))))

(defroute ("/message" :method :POST) () (let* ((body-params (request-body-parameters *request*)) (name-param (assoc "name" body-params :test #'string=)) (message-param (assoc "message" body-params :test #'string=))) (if (and (consp name-param) (consp message-param)) (add-message (cdr name-param) (cdr message-param)) (format t "Missing body parameters: received ~A~%" body-params))) (redirect "/"))

(defroute ("/message/delete" :method :POST) () (let* ((body-params (request-body-parameters *request*)) (id-param (assoc "id" body-params :test #'string=))) (if (consp id-param) (let ((id (ignore-errors (parse-integer (cdr id-param))))) (when id (delete-message id))) (format t "Missing id parameter."))) (redirect "/"))I also added another function, which defines a method on the web app class. on-exception is a generic function called when an exception occurs in the web application. This method is specific on the parameter type, since it will run only if the exception has code 404 — not found — and in that case I return a specific custom template.

(defmethod on-exception ((app <web>) (code (eql 404))) (declare (ignore app code)) (render #P"404.html"))Run the demo

Now I can load the project into the environment with Quicklisp.

> (ql:quickload :guestbook)To load "guestbook": Load 1 ASDF system: guestbook; Loading "guestbook"......................(:GUESTBOOK)CL-USER>Then I can start the server and point my browser to 127.0.0.1:3210.

> (guestbook.core:start)Hunchentoot server is started.Listening on 127.0.0.1:3210.Server started

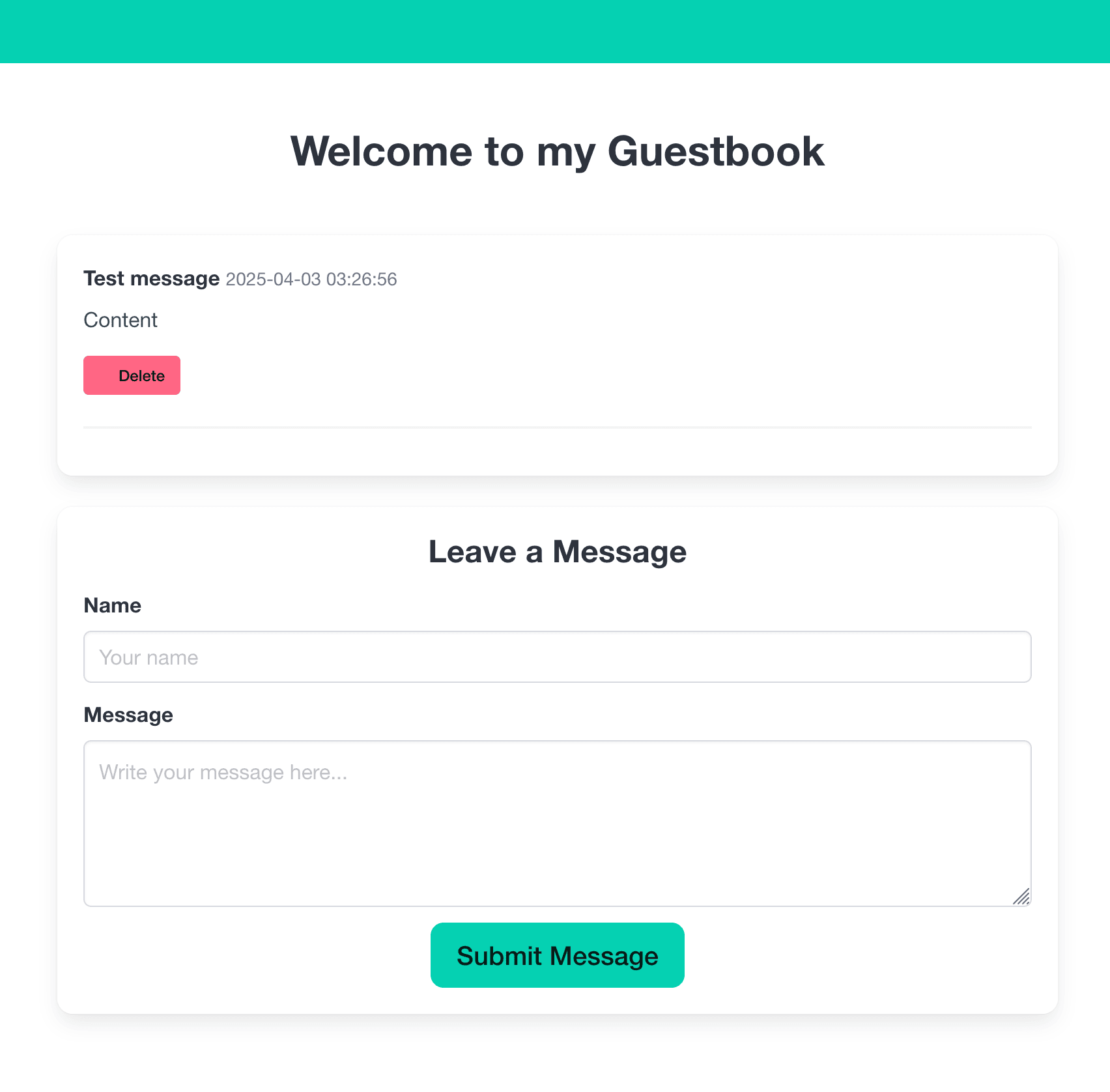

I can send messages that get saved with a timestamp and then delete them. Pretty simple.

Reducing boilerplate

Lisp became popular for a series of reasons, and one of the most cited is its ability to reduce boilerplate thanks to the metaprogramming capabilities of the language. Lisp hackers are proud of being able to code solutions faster and do exploratory programming, reducing the size of the code they need to write to reach a solution.

When comparing the lines-of-code count of my Common Lisp guestbook against the Python-Flask version, the latter seems quicker and simpler to write — 36 lines of Python vs. 229 of Lisp. Lisp’s strength is its ability to model itself according to the problem the developer is solving. In this case, I am dealing with a simple guestbook demo, so it may not be strictly necessary, but to present the language better I will try to reduce the size of the program by hiding some code and configuration.

First, let’s have a look at the new guestbook app, written in my new custom web framework called flashcl: 29 LOC, properly formatted and stripped of all comments, and not too hard to read.

(in-package :cl-user)(defpackage guestbook.core (:use :cl :flashcl))(in-package :guestbook.core)

(init-flashcl :sqlite3 "guestbook.sqlite")

(defmodel message ((username :col-type (:varchar 50) :accessor message-username) (content :col-type :text :accessor message-content)))

(defroute "/" () (render #P"index.html" (list :messages (db-all 'message))))

(defroute ("/message" :method :POST) () (let ((name (form-param "name")) (message (form-param "message"))) (if (and name message (> (length name) 0) (> (length message) 0)) (db-add (make-instance 'message :username name :content message)) (format t "Missing body parameters: received ~A~%" (body-params)))) (redirect "/"))

(defroute ("/message/delete/:id" :method :POST) (&key id) (if id (let ((id (ignore-errors (parse-integer id)))) (when id (db-delete (db-find 'message id))) (format t "Missing id parameter."))) (redirect "/"))Where did start go? It is now part of the flashcl framework, so it’s imported in the package. Here’s the usage reference.

;; --- Run the Application ---;; Call run-app function from your REPL or add it here to run on load.;; Call stop-app to stop the server.;;;; Example: (guestook::run-app) or just (run-app) inside the package.;; (run-app :port 5000 :server :hunchentoot)Then I slightly modified the template delete button to point to the correct route with the id parameter.

I’m going to show just some the new code that I added to write flashcl. I mostly merged the old code in a new file trying to make it as reusable as I could for other web projects, since it’s possible to define new database models and routes quickly, with support for static files and templates. I used mito, another library from Eitaro Fukamachi, which is an ORM that works well with SQLite.

First I imported the library and exported only what’s needed by the user.

(defpackage :flashcl (:use #:cl) (:import-from #:caveman2 #:defroute #:redirect #:*request* #:*response*) (:import-from #:lack.request #:request-parameters) (:import-from #:mito #:dao-table-class ; Re-export metaclass for use in defmodel #:connect-toplevel #:ensure-table-exists #:select-dao #:find-dao #:delete-dao #:insert-dao) (:export ;; Setup #:init-flashcl ;; App Definition #:flashcl-app ;; Variable holding the app instance #:defmodel ;; Routing & Request/Response #:defroute #:form-param #:render ;; Re-export caveman's render (or wrap it) #:redirect ;; Re-export caveman's redirect ;; Database #:db-all #:db-add #:db-find #:db-delete #:dao-table-class ;; Re-export metaclass ;; Running #:run-app #:stop-app))Then I wrote an initialisation function similar to Flask’s, which sets various variables and creates a new instance of the Caveman webapp.

(defun init-flashcl (db-type db-path &optional (template-dir "templates") (static-dir "static")) "Initializes Flashcl environment. Sets DB/Template paths, connects DB." (setf *database-path* (get-absolute-path db-path)) (setf *static-directory* (get-absolute-path static-dir))

;; Set Djula's template directory (djula:add-template-directory (get-absolute-path template-dir)) (format t "Set template directory as ~A~%" (get-absolute-path template-dir))

;; Connect to SQLite database (handler-case (connect-toplevel db-type :database-name *database-path*) (error (c) (format *error-output* "~&Error connecting to database ~A: ~A~%" *database-path* c)))

;; Define the Caveman2 app instance here (setf flashcl-app (make-instance 'caveman2:<app>)))To make it easy to define a new database model for the application, hiding the mito library, I created a macro that ensures the table gets created correctly. mito automatically adds a few fields to the table definition, like id and created_at or updated_at, so we don’t have to worry about them.

(defmacro defmodel (name slots &rest options) "Defines a Mito DAO class and ensures its table exists. Example: (flashcl:defmodel comment ((name :col-type (:varchar 20)) (comment :col-type :text)))" (let ((class-options options) (table-name (string-downcase name))) ; Use singular name by default

;; Add table name inference if not present (unless (find :table-name options :key #'car) (push `(:table-name ,table-name) class-options))

`(progn (defclass ,name () ,slots (:metaclass mito:dao-table-class) ,@class-options) ;; Ensure table exists after class definition ;; Note: This runs at compile/load time when defmodel is processed. ;; Ensure DB is connected before loading code using defmodel. (handler-case (ensure-table-exists ',name) (error (c) (format *error-output* "~&Warning: Could not ensure table for ~A (DB might not be connected yet?): ~A~%" ',name c))) ;; Return the class name ',name)))Then I added some database helpers to perform a few CRUD actions on the db.

(defun db-all (class-name) "Selects all records for the given model class." (select-dao class-name))

(defun db-find (class-name id) "Finds a model instance by ID." (find-dao class-name :id id))

(defun db-add (instance) "Inserts a model instance into the database." (insert-dao instance))

(defun db-delete (instance) "Deletes a model instance from the database." (delete-dao instance))Conclusions

To recap, in this tutorial I used some of the latest libraries in Common Lisp to create a simple guestbook webapp. Then I wrote a simple reusable wrapper to make our code more concise, aiming to challenge the Flask framework in Python. The full source code of the two versions it’s here and here.

Ultimately I would like to give my opinion on using Common Lisp to write a web server. Common Lisp shines when dealing with low-level tasks like small systems programming or performing intensive computation at scale. When these complex systems need to communicate with the outside world, perhaps via an API, writing a server is the correct way and Common Lisp is capable of delivering that.

But despite the fact that the language is easily adaptable and comes with performant server libraries (Hunchentoot and Woo), I would say that there are better alternatives for developing generic modern web apps. Hot reloading is now a feature present in many web frameworks, and Common Lisp is not really shining for being ergonomic, nor does it come with many built-ins. Clojure, by contrast, is a modern Lisp dialect with great web frameworks, nice documentation and tons of stable libraries. I would definitely choose the latter for a fresh web project, since with CL I get the feeling that I would end up having to write more code than I should to add custom features and middlewares.

I would like to give a shout-out to Alive, which is the only Common Lisp extension for VSCode that implements the REPL with features similar to what SLIME and SLY bring to Emacs. The extension is still under development and not yet a full replacement for Emacs, especially during debugging, but it has great features and a lot of potential to introduce Common Lisp to newcomers, thanks to the VSCode web interface.

Feel free to email me if you have any questions, recommendations, or even complaints.