H. P. Lovecraft - Michel Houellebecq

I found a new literary genre with which I feel particularly aligned: biographies of writers written by other writers. By calling it “new,” I don’t mean it’s an emerging trend, but rather a type of novel whose evocative power I had never experienced before. I started with Philip Dick’s science fiction when I read the book about him by Emmanuel Carrère, which I liked so much that it made me passionate about both writers. Now, thanks to Michel Houellebecq’s biography of H. P. Lovecraft, which I just finished, I cannot wait to dive into the renowned Necronomicon, also known as the Book of the Dead.

Houellebecq’s work is not a complete account of the author’s life, like Carrère’s work on Dick, but rather an analysis of the most significant events of his existence, which, in Lovecraft’s case, are quite few. From a young age, he read horror novels and developed a great passion for Edgar Allan Poe, to the point of starting to write stories himself. He had a “nervous” breakdown just as he reached adulthood, which forced him to withdraw from university and lock himself up at home for several years, during which time he did nothing but read. He came from a once-wealthy family that had fallen into ruin, and after the death of his parents, he found himself with a small inheritance, just enough to live without having to work. Lovecraft devoted himself entirely to writing, sending his stories to publishers without asking for payment. He engaged in hundreds of correspondences and managed to create a small circle of admirers of his works. He married an attractive woman, but the initially happy marriage fell apart after a few years due to financial instability and the lack of a steady job—Lovecraft found no stable employment in New York. He returned alone to Providence, to the family residence, and spent his final years in poverty with his sister, working as a ghostwriter and writing his best works. He died of cancer at 46, practically destitute. Success came too late, but when it came, it was magnificent.

"The one thing I never do is sit down and seize a pen with the deliberate intention of writing a story. Nothing but hack work ever comes of that. The only stories I write are those whose central ideas, pictures, and moods occur to me spontaneously.” — H. P. Lovecraft.

Lovecraft appeared to be a bland, calm, and reserved individual, but in reality, he led a double life. In his horror stories, his vivid imagination was inspired by the deep hatred he felt for the inept bureaucrats who couldn’t give him an honest job, for the Black people who infested New York like monsters, and for a society so complex and deeply flawed that it made him feel like a misfit and a failure. Lovecraft was a misanthrope who spent much of his life as a recluse, writing horror stories. His upper-class bourgeois upbringing had taught him to despise not only money but also all classes or races that weren’t up to his standards. In New York, his hatred and disgust for the people of color who crowded the city grew, something he wasn’t accustomed to, coming from the provinces. When he returned home, these experiences of hatred that overwhelmed him became the source of inspiration for his terrifying and monstrous stories, where the protagonists, usually white and refined scholars, are cruelly attacked without any hope of salvation.

“Reading Lovecraft offers a paradoxical relief to all those who, for one reason or another, have come to feel a genuine aversion to life in all its forms.” — Michel Houellebecq.

In New York, Lovecraft sought work, responding to hundreds of ads and attending hundreds of interviews, only to meet with complete failure. Not finding work made him increasingly disillusioned with life, precisely at the moment when he had married the only woman who had ever loved him, with whom he had imagined a “normal” future together, and perhaps a family. The job market rejected him because he lacked the skills and experience, even though he had an academic education and intellectual abilities above the norm. To him, his inadequacy remained a mystery. I want to quote here an excerpt from a circular he sent to multiple employers: “The concept that a cultured and intelligent person could not quickly acquire any skill in a field slightly outside their habits seems to me at least naive; however, a series of recent events has unequivocally demonstrated to me how widespread this superstition is.” The elegance with which he highlights the irrational stupidity of these employers is remarkable. They don’t see individual potential unless it is certified by some kind of institution.

“Howard Phillips Lovecraft serves as an example for anyone who wishes to fail in life and, eventually, succeed in art.” — Michel Houellebecq.

Lovecraft failed in life, but succeeded in writing. Houellebecq didn’t choose Lovecraft just because his stories fascinated him as a boy. He chose Lovecraft because, like him he doesn’t feel part of this world, like him he harbors a deep anger toward a society that doesn’t understand him, and both choose to fight it through literature. One thing I like about biographies written by good writers is when they include personal references in the story. In Carrère’s case, the allusions to himself are more explicit, while in Houellebecq’s book, knowing today the future themes of his literary production, we can see the conclusions about Lovecraft’s work, expressed with intense passion, as veiled allusions to the feelings the two writers share. Houellebecq writes about Lovecraft because he recognizes in him the same fate, the same force that will push him to make his life a work of art through dissident literature.

“Writers of the fantastic are generally reactionaries, simply because they are particularly, or one might say professionally, conscious of the existence of Evil.” — Michel Houellebecq.

This short essay on Lovecraft’s work and life offers a glimpse into his psychology that we couldn’t capture through the reading of his books alone. Houellebecq, as a fervent admirer, offers us a suggestive analysis capable of making us feel both pity and respect for the writer from Providence, while encouraging us, through Lovecraft’s exemplary work, to also oppose the hostility of modern life toward true artists.

“Therein lies the deep secret of Lovecraft’s genius, and the pure source of his poetry: he succeeded in transforming his disgust for life into active hostility. To offer an alternative to life in all its forms, to build a permanent opposition, a permanent remedy to life: this is the highest mission of the poet. This mission Howard Phillips Lovecraft accomplished.” — Michel Houellebecq.

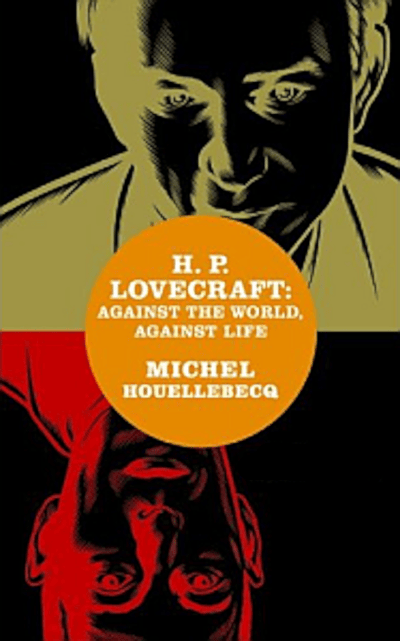

The very fitting cover of this English edition deserves a mention, unfortunately abandoned in subsequent ones. With about sixty years between them, the two artists are united by the inner malaise that drives them to want to take a stand, with their work, against the world and against life itself.